- excerpted from a 1989 article by Dean Grennell

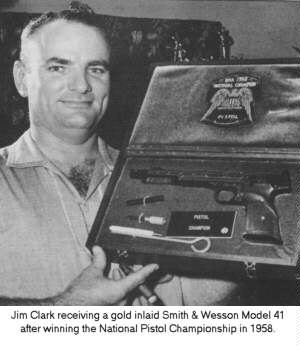

JIM CLARK shot NRA Bullseye Pistol

competition for twenty-eight years, finally retiring from

competition in 1975. Clark won the National Pistol Championship

in 1958 and is the only civilian ever to accomplish this feat. He

won the National civilian title five times. He was the fifth man

in the U.S. to break 2600 and the fourth to break 2650. But his

accomplishments don't end there. He has been fully active in the

pistolsmith business since 1950, well known as one of the true

innovators of pistol accurizing.

JIM CLARK shot NRA Bullseye Pistol

competition for twenty-eight years, finally retiring from

competition in 1975. Clark won the National Pistol Championship

in 1958 and is the only civilian ever to accomplish this feat. He

won the National civilian title five times. He was the fifth man

in the U.S. to break 2600 and the fourth to break 2650. But his

accomplishments don't end there. He has been fully active in the

pistolsmith business since 1950, well known as one of the true

innovators of pistol accurizing.

In 1985, the American Pistolsmiths Guild awarded Clark a trophy

proclaiming him American Pistolsmith of the Year. Bagging double

brass rings as the best pistol shooter in the country and its top

pistolsmith is a unique coup: accomplished by James Edwin Clark

and by no other known human being. I would say it serves as more

than adequate excuse to feel a bit chesty about things.

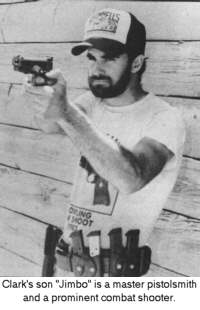

Mrs. Clark works in the office in the shipping-receiving

department and they have a son, Jim Clark, Jr., who' s also a

pistolsmith and shooter. The younger Clark racked up his first

listed win in 1971, his twenty-eighth in 1988. Give him time and

he may catch up with his sire, but that's a tough row for anyone

to hoe, though his genes should be helpful.

The story of Clark's early years constitutes one of those

triumphs over bleak adversity through sheer guts and

perseverence. He was born on the fifteenth of February in 1923,

down in Fort Worth, Texas. When he was 3 years old, his father

deserted his mother and her brood of three. She struggled to keep

the family intact as best she could, working as a seamstress.

After a time, she remarried and, from Jim's viewpoint, everything

didn't start coming up roses, as of that moment.

His stepfather wouldn't allow Jim to own or fire guns during the

lad's early years. The children had no toys other than what Jim

was able to construct and share with them. Put another way, when

the basic alloy is just right, adversity can serve as the

tempering agent that, somehow, produces an uncommonly remarkable

human being. Browning certainly was one example and Clark is

another. Does this mean we should set up homes for

over-privileged children and systematically mistreat the wee

nippers so they' 11 grow up to be the leaders and innovators of

generations to come? I hasten to note that I'm being facetious...

probably.

Despite being 8-1/2 months older than myself, Clark made a more

routine passage through the school system and graduated from high

school in 1942, rather than 1940. We both went into uniform in

'42, however.

Clark wanted to be a Navy pilot, but the swabbie docs thought

they spotted a trifling defect in the cartilage of his nose and

declined his offer. So he went around to palaver with recruiters

for the U. S. Marine Corps, all too innocently unmindful that

they "take" from the USN.

A glib-tongued Marine recruiter solemnly assured Clark that, if

he'd only sign the paper and hold up his right hand, he'd go off

to pilot training straight as a shot. So Clark signed up and they

zipped him off to training...as a rifleman.

Clark's family had moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1939, about

the time he got into high school and his favorite course had been

mechanical drawing getting nothing but straight A's for that on

his report card. He'd also joined the ROTC and became the captain

of its rifle team. Thus, the USMC's arbitrary assignment wasn't

all that grotesque. All they really did was nail the feet of a

would-be birdman to terra ever-so firma.

Clark got through USMC boot camp and was assigned to Camp Elliot,

California, for scout/sniper training with the newly organized

4th Marine Division. Graduating with honors from that program,

Clark saw service at Roi-Namur and Saipan with the division.

Scout/ snipers serve as sort of the eyes and flashing fangs of

combat USMC groups; a spectacular but small band of specialists.

Most of Clark's duties were carried out well in advance of the

American lines.

He was issued a Springfield with a 10x Lyman target scope sight

and came to like the rifle, meanwhile feeling somewhat less

warmth toward the unwieldy and painfully vulnerable scope. During

the Saipan landing, he stashed the scope in his pack and later,

on unpacking it, discovered it had been demolished by a shell

fragment, even though he didn't have so much as a scratch.

He discarded the sightless Springfield in favor of a scavenged

M-l Garand and an M1911A1 pistol, dealing himself into the

surrounding fray. After a time, he acquired another Lyman-scoped

Springfield from a sniper who'd collected some punctures and was

being retired from cornbat, thus putting Clark solidly back into

business as a scout/sniper.

As Clark' s unit came up on the small village of Garapan, Clark

had lost three different spotters to enemy fire. All by himself

and unattended, he perched alone upon a cliff, a thousand yards

or so above a road leading out of the village.

The road below was all a-crawl with Jap troops engaged in a

frantic bugout. Clark managed to get his new scoped Springfield

sighted in for the generous distance and fired over three hundred

rounds, scoring nothing but hits after he'd "found the

range." It seems likely he accounted for more enemy soldiers

than he would had he gotten his original wish and won his wings.

Clark put in twenty-one days of combat before catching a rifle

bullet in the shoulder as he attempted to rescue a wounded

partner. He was sent to the hospital and his left arm was

paralyzed for six months. He spent the next year in various

stateside Naval hospitals before receiving a discharge in 1945.

Returning to Shreveport, Clark enrolled in college, majoring in

architecture and took a job after classes, working part time in a

local gun shop.

It was in 1947 that a friend invited

Clark to shoot in a pistol match. Using an as-issued GI Remington

Rand .45 auto and hardball military ammo, Clark chalked up a

seventy-eight percent at fifty yards on his first try.

Considerably intrigued, he borrowed the needed three guns --

a.22, a .38 Special and an accurized .45 auto -- to enter a

registered NRA match. He qualified as sharp shooter and made

expert in his second match, master in his third. Many pistol

shooters work for grim and dogged years to achieve master rank

and a lot of them never make it.

It was in 1947 that a friend invited

Clark to shoot in a pistol match. Using an as-issued GI Remington

Rand .45 auto and hardball military ammo, Clark chalked up a

seventy-eight percent at fifty yards on his first try.

Considerably intrigued, he borrowed the needed three guns --

a.22, a .38 Special and an accurized .45 auto -- to enter a

registered NRA match. He qualified as sharp shooter and made

expert in his second match, master in his third. Many pistol

shooters work for grim and dogged years to achieve master rank

and a lot of them never make it.

When Clark shot his first score over 2600 -- out of a possible

2700 - he did it with borrowed guns, except for the Colt Match

Target .22 he'd bought second-hand for $50. It was 1950 when

Clark broke 2600 and 1960 when he became the fourth man to top

2650.

With the outbreak of the Korean War, Clark was called back into

service in 1951 and spent considerable time at Camp Pendleton,

California, doing accuracy jobs on Marine competitors' .45

pistols. He encountered a .38 Super Colt that had been converted

to handle the .38 Special wadcutter and was thoroughly fascinated

by the prospects he saw in it.

Upon his discharge in late 1951, Clark went back to Shreveport

with a Sheldon lathe and milling attachment he'd purchased for

$600 from a Marine gunner. His friend Bill Gooch -- the same one

who had introduced him to pistol shooting in the first place --

Loaned him money and helped him set up a building.

Clark arranged a bank loan and bought twenty .38 Super Colts,

converting them to handle the .38 Special midrange wadcutter

cartridge. He ran an advertisement in the American Rifleman and

it drew a heavy response from interested would-be customers. The

Clark name quickly became known among pistol competitors and

there has been heavy demand for his products and services ever

since.

Despite the time and effort of maintaining a successful business,

Clark continued as an active competitor. Goaded by the heavy

traveling entailed in match shooting, Clark learned to fly and

bought an airplane, thus finally realizing a long-term ambition.

During the years as a match competitor,

Clark spent upward of $10,000 a year on match fees, travel

expenses and practice ammunition. There are some who do not need

a great deal of practice, but Clark admitted he is not one of

them.

During the years as a match competitor,

Clark spent upward of $10,000 a year on match fees, travel

expenses and practice ammunition. There are some who do not need

a great deal of practice, but Clark admitted he is not one of

them.

His top place in the U.S. Open Pistol Championship in 1958 was a

singular achievement, as Clark was the first shooter to win that

event without being sponsored by a military or police group. He

footed all of the considerable expenses out of his personal

pocket and, yes, he feels it was worth it.

It was 1975 when Clark finally decided the game was no longer

worth the candle and retired from the competition circuits so he

could devote full time to running his shop. One of the house

specialties was a target conversion of the .22 LR Ruger auto

pistol to which he fitted a steel trigger of his own design, as

well as stocks and barrels. He has turned out close to 30,000

such guns, along with nearly a quartermillion .45 accuracy jobs

and .38 Special Colt conversions.

As time permitted, Clark made a number of experiments aimed at

improving performance of the .45 ACP Colt. Among the things he

discovered was that six inches probably represents the ideal

length for the barrel. He began using Douglas barrels that

incorporated an integral feed ramp of his own design. The novel

concept served two vital purposes: First, it cured a lot of the

feeding problems that stem from the juncture between the feed

ramp at the upper front of the magazine well and the relieved

area at the lower edge-of the chamber. Second, it supported the

case head and thus prevented the occasional problem from blown

case heads. Clark eventually manufactured such barrels entirely

in his own shop.

Another Clark innovation was the

long-slide conversion and that came about rather fortuitously.

Visiting a war surplus store in Arkansas, Clark came upon an

entire oil drum full of GI pistol slides that had been cut in two

by the government in the process of deactivating service pistols.

Clark bought the entire lot of destroyed slides for a dime apiece

and spent the next several years turning them into long slides.

With the supply finally exhausted, he had them made from scratch

by an outside vendor.

Another Clark innovation was the

long-slide conversion and that came about rather fortuitously.

Visiting a war surplus store in Arkansas, Clark came upon an

entire oil drum full of GI pistol slides that had been cut in two

by the government in the process of deactivating service pistols.

Clark bought the entire lot of destroyed slides for a dime apiece

and spent the next several years turning them into long slides.

With the supply finally exhausted, he had them made from scratch

by an outside vendor.

With the advent of bowling pin competition in the mid-Seventies,

Clark came upon another area of endeavor. He produced what

probably was the first auto pistol expressly designed for that

challenging event, As refined and finalized, the Clark pin gun

has a coned sleeve at the muzzle extending in front of the slide

and the same width. At the buyer's option, it can have

recoil-control vents or it can be plain, with a choice of 5-1/4,

5-3/4, or 6 inch barrel lengths. Several other helpful features

can be had such as a bevel around the base of the magazine well,

stippled front strap, low-mounted sights by Millett, Bo-Mar or

others, extended ejector and a lowered ejection port,

Jim Clark was also an enthusiastic hunter and has taken dozens of

deer, using an iron-sighted Model 29 Smith & Wesson with an

8-3/4 inch barrel, along with a great many smaller game species

bagged with assorted other handguns.

To read more about Jim Clark and the company he founded, Clark

Custom Guns, visit their website at www.clarkcustomguns.com.

Up until the day he died, Jim and company faithfully made the

trip to Camp Perry every year.